Reality in the Food Pantry

“How did we all fit?” What is the reality in the food pantry?

New shoppers always had funny looks on their faces the first time they shopped at the pantry. They expected to fill out forms. They expected to prove through documents they existed, had an address, and deserved the food.

They brought social security cards, utility bills, pay stubs, birth certificates. They came prepared to surrender their innermost private lives in exchange for recycled food originally rejected by a farmer, food manufacturer, grocer, wholesaler. It was all bound for a landfill.

The pantry didn’t have much in the way of screening procedures. For intake, shoppers signed their names and wrote the number of seniors, adults, and children in the household.

Nobody showed documents, especially not their social security cards. Our forms didn’t ask for addresses because the first inspector to visit the pantry after I became the coordinator assured me they weren’t necessary.

On pantry day, hungry people lined up and went through the pantry as fast as we could process them. In the two-to-three minutes they had in the room, they took their share of everything on the shelves, regardless of what it was. I never saw a person turn up a nose at canned peas, fresh spaghetti squash, or beets.

Pantry food is a shock to hungry people on their first visit. They see unrecognizable items. They sometimes sought a realitycheck. They don’t know what they’re called, how to prepare and eat them, how to store them. They have no idea what the nutritional content is.

Often, ethnic shoppers have no money and are separated from anything and everything they know or experienced. Undocumented citizens have no money, know few or no people, probably can’t speak the language, and they are forced by circumstances to shop in a pantry offering nothing familiar to eat. This must be a lonely feeling. They questioned the reality of their circumstance.

Worse, finding ethnic food, kosher food, Asian food, is simply not going to happen in a pantry. This is not necessarily by design. Food pantries only have food available to them that the food bank has to share. And, of course, the food bank shares what is donated.

At the end of the shift on pantry day, in the quiet of the closed pantry room, I counted totals. I carefully added the children, adults, seniors, and households in the pantry line that day. Often I was surprised at the end of a shift that such large numbers of hungry people shopped in the pantry in one afternoon.

The State of New York sent down clear guidelines, rules, conditions about what, how, and when pantries distributed food donated to hungry people.

Produce came from area farms. The Hepworth Farm, the Patroon Farm (owned by the Food Bank of Northeastern New York), and Migliorelli Farm as well as from other area farms throughout the Hudson River Valley, throughout the nation, and from foreign countries even. Farms grew and gave beautiful, fresh, clean, colorful, aromatic produce.

Produce made its way from a farm to a wholesaler, food manufacturer, and finally, a bakery or grocery chain in New York State. Food manufacturers, wholesalers, farmers, supermarkets salvaged food and donated it to the food bank. And that’s where the food banks came in. Food pantries received rejected food anywhere along the food chain. Volunteers put it on the shelves, and distributed it to hungry people lacking money to buy food.

Most fresh produce came directly to the food bank and what received was often organic but not labeled. It costs money to label produce as organic. The stickers alone cost money. Paying someone to apply them is another cost. The reason against labeling the produce is practical. Labeled or not, this beautiful food kept shoppers from feeling they were getting rations. That’s how the State of New York wanted it.

Not all Hudson Valley farms used organic methods. Migliorelli Farms, for example, didn’t label produce as organic because this family-owned farm used European agricultural standards to reduce health risks and exposure to pesticides by incorporating crop rotation, fertilization, irrigation, and planting systems.

Never ours, the food was in our safekeeping to give to hungry people, homeless people, the mentally ill, physically ill, poor, to anyone in need. Leastways, that was what I thought we were supposed to do with it.

New York State tax dollars worked in the pantry. When volunteers worked at the pantry, we did so willingly and for free.

Sometimes I thought I was the only one in town to see it this way. Many felt I fed the unworthy hungry, that I embraced the wrong people. None of the food boxes came to the pantry stamped Worthy Hungry Only. I never understood what unworthy hungry meant, who the unworthy were, where they came from. I didn’t understand unworthy hungry the same way I didn’t understand rocket science. I just didn’t get it. Because I didn’t get it, no one could sway my beliefs.

Instead, I understood hunger, giving, receiving, sharing, and abundance. When people signed their names and accepted food, miracles rippled out beyond the building, beyond walls and boundaries – to a divine experience.

While shoppers got food, they sought the resources to live meaningful lives and to trust there was something to believe in, cling to. They sought the focus to rebuild lives.

At the pantry day’s end, I was thankful people got groceries.

I searched and searched and got beyond hunger and abundance. My search was about the meaning of life. In my youth, (in my thirties), I asked two questions: What is the meaning of life? Whatever happened to the Anasazi?

In the pantry (in my seventies), I still searched for the meaning of life. My questions were different: How did I end up in a food pantry at my age? Who are the unworthy hungry. My questions were wrong. What I should have asked was “why”, now “how” or “who”.

All my life I felt when I got to be a woman of a certain age I would sit in the rocking chair I inherited from my grandmother and learn to knit or crochet. Maybe I would occasionally venture beyond home in my yellow Volkswagen convertible with a black top to paint a picture or two in a class nearby. I fantasize the top would be down at every outing to free my cotton top curls.

Instead, I worked in a small town food pantry in the midst of the biggest economic downturn for decades.

I managed a food pantry in a community where some weren’t interested in recognizing poverty and hunger existing under their very noses.

It came down to reality. I never found discovered the unworthy hungry because I never saw anyone in the pantry who didn’t need food. Those preoccupied with feeding with the unworthy hungry saw freeloaders who didn’t need the food, or didn’t belong in the line.

I saw grandmothers and mothers with children standing in the line without uttering a sound. Not in my wildest dreams did I figure out how they got the children to be so quiet and stand so still. Grandparents, aunts, uncles, siblings, and close friends stood in the line for as much as an hour on Wednesday or Thursday afternoon with children, mostly preschoolers.

Caregivers stood in the hallway weekly in cold, wet, dry, rain, snow, broiling heat inching their way down the long hall until their turn came in the pantry room. No one, either child or adult, complained about the freezing cold hallway in the winter where the only warmth came from the body heat of fellow shoppers. The nearest I ever got to a complaint was volunteers and shoppers wearing two hats in the winter. No one, neither adult nor child, complained about the oppressive summer hallway heat. The children never made a peep.

Many lived on fixed incomes unprepared for the financial costs and emotional roller coaster ride involved in raising someone else’s children. Ready or not, they cared for children when the biological parents couldn’t. For some, the situation was overwhelming. For others, it was just another day.

THREE SHOPPERS

I saw a cancer patient with finances reduced to a large box filled with bills and no money in the bank. He shopped weekly until his death.

I saw the woman whose brother had Alzheimer’s. She was his caregiver and he couldn’t be left alone. Sometimes she arrived at the pantry so disheveled it was difficult for her to stand in the line and shop. One afternoon she crashed her car into the bridge outside the pantry entrance.

I saw the widow with more month than money who refused to go to her children for help. She visited the pantry regularly. One shopping trip included the first anniversary of her husband’s death. She kept her pantry trips a secret from her children because she was embarrassed to let them know. This was a small community, so they eventually figured things out.

THE MOTHER AND GRANDMOTHER

She brings her young granddaughter to the pantry weekly. Sue is maybe four. She is shy. Dark brown ringlets frame her little cherubic face. Her expressions and posture tell me she’s still unaware of her situation. Her mother works two plus jobs. There’s not enough food to eat in this household. Her little dresses are threadbare.

This lovely child takes pleasure in the smallest gifts. Today, her treat is a can of juice a volunteer found in the storeroom that’s not dented. Her grandmother teaches her to stand in line quietly, smile, and say “thank you.”

When I see them, I see the universal mother and grandmother next door. I see a mother and grandmother working hard so that adorable little child has access to a good school, health care, safe streets.

They are our neighbors.

They are our family.

They are us.

I’m reminded we do not live in a we/they world.

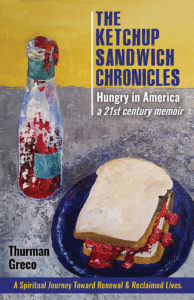

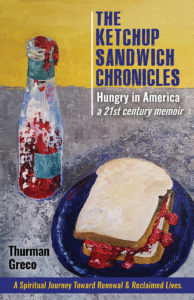

Poverty hits children especially hard, with long-term consequences for behavior, learning, and mental health. They suffer the effects of going to bed hungry. Ketchup sandwiches and bowls of dry cereal don’t offer the nutritional strength a child needs to grow up into a healthy adult.

However this shakes out, the hungry are us.

Thank you for reading this post. Please refer it to your preferred social media network.

Thurman Greco

alleviating hunger, cash flow, Disaster Preparation, domestic violence and sexual assault survivors, elderly poor, emergency feeding programs, emergency food assistance, emergency food assistance program, employed poor, fear, feeding the homeless, Feeding the Hungry, food desert, food insecurity, food insecurity for seniors, food pantries, food pantry, food pantry blog, generational poor, global warming, homelessness, hunger, Hunger is Not a Disease blog, ill poor, infant poor, meaning of life, medical expenses, meditation, mental illness, nutrition assistance, persistent poor, protection, resource poor, serious illness, situational poor, SNAP, social justice, soup kitchens, struggling poor, the transportation challenged, Thurman Greco, transportation challenged, trauma, trauma sensitive yoga, underemployment, unemployment, waste disposal, Woodstock NY